Blog

By support

•

November 4, 2024

I wrote The Wild Ones with memories of my adolescence as part of a violent community in my hometown of Monterrey, and also with the memory of a very complicated area on the outskirts of my city that I got to know around that time. That place is called El Peñón, located at the foothills of Cerro de la Silla, an emblematic mountain of my city. The houses are clustered on the slopes, next to ravines, among the rocks. Poverty is severe there, and the needs are many. It's an ideal place for organized crime gangs involved in drug trafficking to recruit young people into their ranks. But at the same time, it’s a happy place; people live as they please, social relationships are as good and bad as anywhere else, and there are also boys and girls who, despite the poverty, choose to study and get ahead. The Wild Ones tells the story of a boy at a crossroads: his mother is unjustly imprisoned, and he must find a way to get her out—either through the regular judicial system, which offers nothing, or by joining forces with the drug trafficking gangs, who at least promise to protect his mother in prison. And it's also about the main character, Efraín, and the relationship with his siblings and the choices they make along the way. As this unfolds, the novel portrays the city, what it's like to live in that area, and the struggle to escape poverty—all seen from two perspectives: the raw, real view of the drug world among young people, and a festive, casual, joyful view that shows what it's like to live and push forward from that situation. The Wild Ones will take you through a world beyond the bleak context of Latin America's large metropolitan cities, leading you on a journey that is real, rough and sad, but also as joyful and hopeful as books can be. Also, I'm thrilled to be part of HopeRoad and to have the novel reach an English-speaking audience with the support of an English PEN Award! Thanks to my editor, Rosemarie, and my translator, Claire, for everything! Time to celebrate. By Antonio Ramos Revllias November 2024, Mexico The Wild Ones was published October 24th 2024 You can find your copy here .

By support

•

October 22, 2024

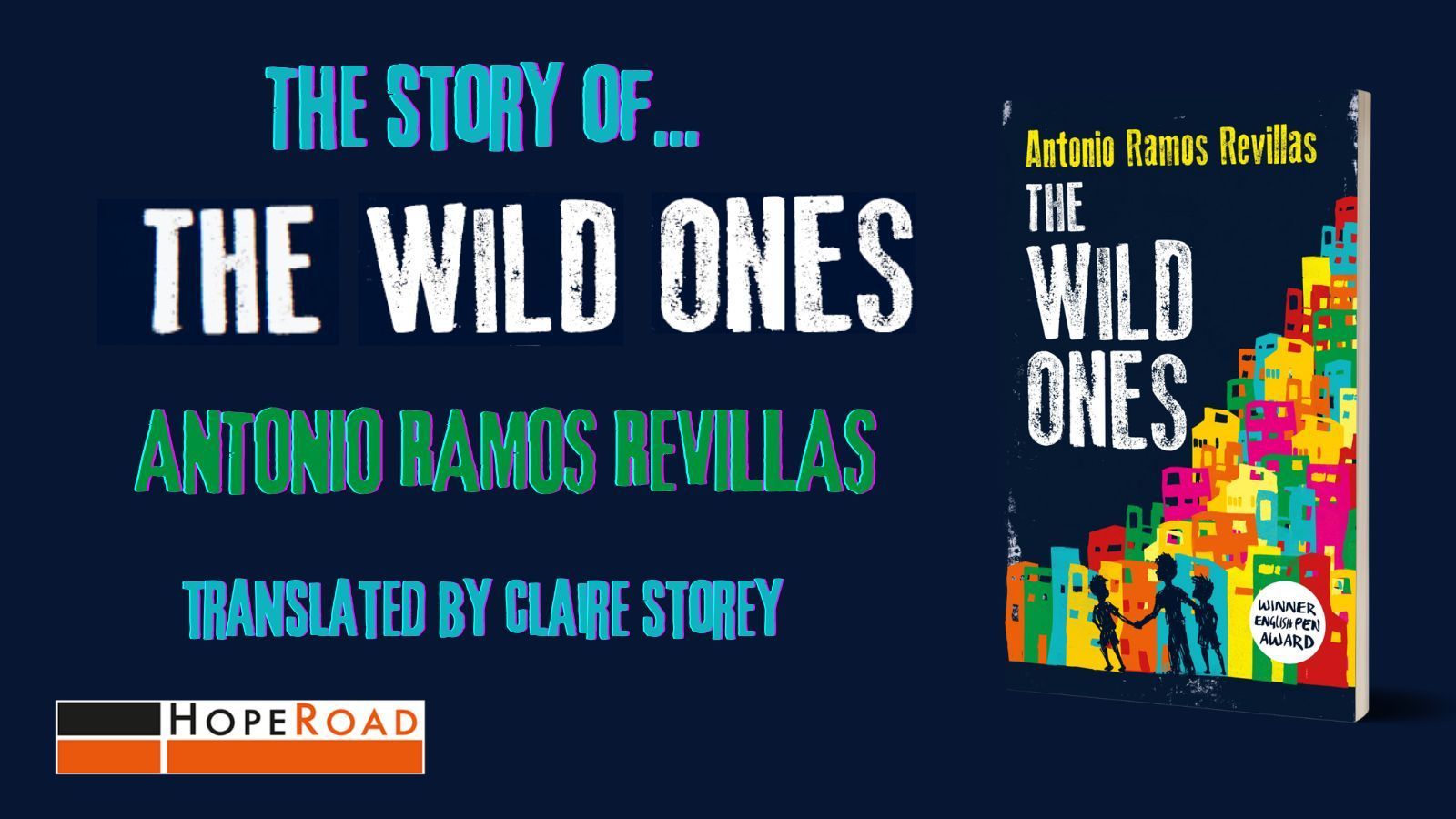

To celebrate the publication of Cauvery Madhavan's The Inheritance , author Cauvery Madhavan has chosen her favourite Irish bookshops to highlight for this year's Irish Book Week 2024. You can explore the map of these bookshops on our dedicated Google Maps , as well as the list below: Cauvery Madhavan's favourite bookshops No Alibis Bookstore ( @NOALIBISBOOKS ) Botanic Avenue, Belfast Antonia’s Bookstore ( @AntoniasBooks ) The Gate House, Navan Gate, Townparks North, Trim, Co. Meath Tertulia Bookshop ( @TertuliaBooks ) West Port, County Mayo Kenny’s Bookshop & Art Gallery ( @KennysBookshop ) Liosban Business Park, Tuam Rd, Galway City, Co. Galway Chapters Bookstore Dublin ( @chaptersbooks ) Parnell St, Dublin 1, Co. Dublin Gutter Bookshop - Dalkey ( @GutterDalkey ) The Gutter Bookshop, 20 Railway Road, Dalkey, Co. Dublin The Maynooth Bookshop ( @MaynoothBooks ) 68 Main St, Maynooth, Co. Kildare Ravens Books ( @ravenbooks ) 34 Main Street, Blackrock, Co. Dublin Woodbine Books ( @WoodbineBooks ) Lower Main Street, Kilcullen Hodges Figgis ( @Hodges_Figgis ) 56-58 Dawson St. Dublin 2, Co. Dublin Bantry Bookshop ( @BantryBookshop ) William St, Town Lots, Bantry, Co. Cork Vibes and Scribes ( @vibesandscribes ) 21 Lavitt's Quay, Centre, Co. Cork The Nenagh Bookshop ( @NenaghBookshop ) Nenagh North, Nenagh, Co. Tipperary Dingle Bookshop ( @DingleBookshop ) Green Street, Dingle, Co Kerry Explore Cauvery Madhavan's titles The Inheritance and The Tainted .

By support

•

September 18, 2024

In the summer of 1999, I drove over the Cousane Gap and, cresting the narrow mountain road, laid eyes on Beara for the first time - the glory of its mountains, valleys, forests and bays stretched all the way to the distant horizon. I was in West Cork to make a start on this thing called writing-a-book that I’d been stewing over for ten years or more. By the time I got to Eyeries at the tip of peninsula, I was head over heels in love. Huge banks of clouds roiled over the Atlantic before scudding across the shimmering expanse of Bantry Bay. In the embrace of the seascapes lay vistas that were in equal measure peaceful and inspiring as they were wild and distracting. It wasn’t long before I discovered that natural elements are the most temperamental of artists - their seasonal whims, their daily fancies, their hourly moods paint, sculpt and colour Beara with wonderful abandon. There is something about the untamed landscape, it’s geological formations and fantastical mountains extruded like slabs of untidy Viennetta, folded, scrunched, squeezed and hewn by volcanic and glacial activity millions of years ago, that energizes from within. The precious pockets of ancient Atlantic rainforest that dot the peninsula, pristine beaches and mystical standing stones come together to form a creative cocoon. Now, twenty five years later I know that my writer’s heart and soul has lived its best life in our small mountainside cottage on the Caha range. There is a peace and quiet that frees the mind though the views are actually very distracting and my writing is usually done facing a blank wall! Being a writer leaves you prone to periodic bouts of writer’s block. This is good because it allows you to be creative with the solutions. They don’t have to be sensible or logical, they just have to work. There is no point in telling a writer not to procrastinate - that’s like telling a monkey not to scratch. It doesn’t help to ask a writer to get a grip, we might let go of the only straw we are clutching at. After all, if you have writer’s block at least it affirms your belief that you are a writer. My solution is to immerse myself in the Beara landscape, to let its ancient magic work on my senses. The old sash windows may be single-glazed, with stiff catches and beads of condensation glinting in the early morning sun, but beyond it is the Ireland I love. Downhill from the house, the Glengarriff river rumbles over a huge rocks, moving swiftly past banks of sally willows in a headlong rush towards the harbour at Blue Pool, a few miles away. The green collage of hillside pastures often fades away behind a fine mist and bands of rain follow, driven in sideways sheets by a whippy wind. Yet a clearance from the West is inevitable, rainbows arch across the valley and the writing begins to flow once again. Coming from India and now having lived in Ireland for nearly four decades, a double dose of national hangups colour my writing. The country of my birth and the country I call home have a shared obsession with family, religion, politics and not making a show of yourself. Stories thrive in this heady mix of plot possibilities and for the last twenty years while I wrote and published three other books, I constantly mulled over the characters in my new novel The Inheritance. Fascinated by the tragic history of O’Sullivan Beare and his people, I was determined to work that story into a thread that ran through the book. I finally began writing it during the first few weeks of the Covid pandemic, using our own cottage as the setting. Then, in the break between lockdowns, having decamped from Kildare to Glengarriff, I stumbled across the most incredible piece of information that literally made my hair stand on end. The narrow and remote mountain ridge on which our cottage is situated actually straddled the ancient battlegrounds of the very siege that I was trying to weave into my story! This discovery, that in the winter of 1602, the English army had camped in the swampy forests in the valley the left of our cottage, while in the valley to the right, O’Sullivan Beare and his followers had remained hidden for six months, was exactly the sort of impetus I needed to spur my writing on. From thereon, I felt that I had to and was meant to write this book, to honor the memory of those many hundreds who perished in what is now the Glengarriff National Forest. Writing might be a solitary pursuit but I believe not much is achieved in isolation. In Beara, I’m lucky to be surrounded by friends who are very protective of my writerly ambitions. This really matters because most writers, some time or the other, are just a sentence away from throwing in the towel. My immediate neighbours have been incredibly supportive and if I headed into Caseys in Glengarriff, Donal Deasey the landlord would inevitably give me bits of information, both historical and contemporary, that added to the scaffolding of my novel as it progressed. It doesn’t surprise me one bit that a thread of magical realism runs though The Inheritance - conceived in Beara it could be nothing else! by Cauvery Madhavan The Inheritance publishes September 19th

By support

•

July 15, 2024

Are we who we are because of the country we were born in, the parents we were born to, the social class we belong to? Or is it because of our lived experiences, our childhood, the things that happen to us and shape our lives? Or is there something else beneath it all, something deep down, a distinctiveness that defines us and makes us unique? These are the questions that led me to create The Darkness of Colours . I have always questioned the decisions I take, wondering whether I am making choices based on my own authentic will or whether I am influenced by factors I have not chosen. Sometimes it is hard to tell these things apart. For example, I love mate (pronounced, mah-tay). Mate is a herbal infusion, drunk from a round bombilla using a metal straw, and it is a very popular drink here in my country, Argentina. In fact, as I write these words, I have a mate on the table next to me. Given this is a local custom, little known beyond Argentina and Uruguay, if I had been born elsewhere, I might not even know it exists. I wonder then, do I like mate because I truly like mate , or do I like mate because we Argentinians drink it from the moment we get out of bed? I believe in the power of fiction and the power of questions, and I like to combine them. It’s 1885 in Buenos Aires. A man kidnaps five babies and embarks on an experiment: to raise each child in a different way and observe the results. In order to avoid any sentimentality, rather than a name, he gives each child a colour: Green, Blue, Black, Brown and White. They are cruel experiments. One of the children is brought up to believe he is a dog. Another is deprived of daylight and forced to fight against wild animals. Twenty-five years later, the kidnapped children return, but they have no memory of where they have been. A journalist is brought in to investigate and as he starts to delve into the case, the perpetrators of the experiment begin to turn up dead. This is a brief summary of the plot of The Darkness of Colours and, as I previously mentioned, my desire was to write about this elusive topic called identity. My initial plan was to write a short story, but I soon realised I had enough ideas to make it a full novel. I thought it would be interesting to situate the events in the past, specifically at the turn of the twentieth century, in part because carrying out the same experiment today would involve topics such as genetics and other technological issues which I was not so interested in discussing. For me, these years – 1885-1910 – are also among some of the most interesting in human history. It is a moment of great scientific advancement, during which a large part of the modern world as we know it today was configured. It is the period when the avant-garde emerged, when artists decided a picture can show more than what we see with our eyes alone, when musicians began to abandon traditional harmonies and writers realised that a novel or a tale can do more than simply tell a story. And to that we add the arrival of cinema, psychoanalysis, Marxism, ultimately new ways of viewing the world that still influence us today. They were years when the word “progress” was used for everything, where humanity placed all of its hopes in a future which, just a few short years later, would be shown to be not quite so brilliant. This was therefore the perfect moment for a man like Andrew to embark on his experiment in search of discovering the true capacity of human beings. I decided the novel would open and close around the festivities celebrating the first centenary of Argentina as a nation in 1910. Are countries themselves not great experiments? At times, that’s how it feels here in my country, at least. Argentina is a country where immigration plays a fundamental role. Around the turn of the twentieth century when the book is set, thousands of people from across the globe – most of them poor – arrived in Argentina with nothing but the hope of making themselves a future in the “New World”. That’s how it was for my family. My grandparents and great-grandparents belong to that world of immigrants I describe in the novel. My paternal grandfather came from Spain with absolutely nothing at the age of just 14. In the same way, my maternal great-grandfather arrived from Italy. I am a product of this immigration. I have included many details about the difference spaces in my city, about the architecture. I decided to use the same streets where I live, the old part of Buenos Aires, and I had to spend a lot of time investigating how my city was back then. It was great to walk the streets I have walked along my whole life, dreaming about how they might have been more than a century earlier. If I am honest, I never thought that this book would reach so many readers so far away. To my surprise, it is now being read in many countries with identities and customs that are completely different to my own (countries for example, where they don’t drink mate ). For me, it is a story so deeply tied to my city that I struggled to believe that anyone outside it would be interested in reading it. Perhaps we are not so different. Perhaps the important questions are the same. I am immensely grateful to anyone who decides to read this book and I hope you enjoy the story. While it is completely fictitious, at the same time it is a postcard from my country, my city and our history. In all its colours. And all its darkness. By Martín Blasco Argentina, 2024 Translated by Claire Storey The Darkness of Colours - July 18th

By Federico Ivanier

•

October 11, 2023

Sometimes people want to know where writers get ideas from. That question always gets me thinking. Where do I really get ideas from? I also ask writer friends the same. I get the impression, every time, that we don’t really know. It’s part of the mystery of writing. And it’s great that it is so. I don’t believe there’s a mechanism to get ideas. Or some kind of imaginary pond, where we can fish a silvery, slippery fish-idea. That would be great, since I would know, as a writer, that I definitely will get new ideas. Because, the truth is that, after I finish one book, I never know if I will write another one, if another idea will be good enough. There’s this unpredictability that writers have to deal with. Once you know, say, how to drive a car, you can drive any number of cars. Once you write a novel, it’s safe to say that it’s unclear whether or not you will be able to write another one. Or, at least, one that you (and publishers) think it’s worth publishing. I have come to think that somehow - maybe - the process is reverse. It’s not you getting ideas, but ideas getting to you. Argentinian writer/legend Julio Cortázar said that the stories that he wrote already existed and that his job as a writer was to turn them into language. So, it’s ideas that get you, not the other way around. That’s a funny way to think about it. It gives the impression that ideas are creatures that haunt or possess writers. At their own will, I might add. Which, of course, is the bothersome side of the deal. As for me, I find the idea both true and impossible at the same time. I am willing to accept that, within all that inexplicability of the appearance of the idea, there’s a part that is not up to the writer. That much I will admit. It doesn’t depend on how much you try to have an idea. It will come. Or it won’t. I would say ideas are, at least in my experience, a mixture of things. On the one hand, they are a state of mind. Let me explain. The very fact that you are in the world as a writer, that you never stop really working as one, or thinking as one, will arrange your mind in a certain way. You will perceive life not just of a set of experiences, but as a set of writing opportunities. For example: my girlfriend left me. I am devastated. It’s terrible. But wait a minute, surely I will be able to write about this at a certain point. That’s the great part of being a writer. You can use experiences to your advantage. If your mind is ready to think about the world in terms of story, you are ready to find it. That is, if your mind is searching (normally unconsciously), it’s bound to find something. That is very much the case with my novel Never Tell Anyone Your Name , beautifully translated by Claire Storey. The story came in a completely unpredicted manner. I was travelling with my then-girlfriend from Bordeaux to Madrid by train. In one point, we had to change from the French train to the Spanish train right on the border. When we were ready to get on our Spanish train, we discovered that the dates of our tickets were wrong: they were for the following day. Changing them for the train due to depart at four in the afternoon (the one we had plans to take) was impossible. It was the end of the holidays and the train was full. The best we could do was get a couple of tickets for the midnight service. So we were left with eight hours of nothing ahead of us. We were in a small town called Irún, which we had never intended to visit and my girlfriend certainly wasn’t interested in visiting. As for me, I was delighted. It was an unplanned event. It was a small event, all right, but unplanned. I decided to visit this place which was not precisely touristic. As I said before, my girlfriend was not really in, but it was worse to remain in the station, so we went. I knew, as soon as I was out, walking (it was a really cold day), that I was going to write about that. I didn’t know exactly what I was going to write, but I knew I would. That very moment was one that I was going to turn into some kind of story. I even took pictures, as we walked, to be able to remember the places we saw, the path we took. I was, already, in a way, taking notes. Of course, it was not that I had the idea ready just then. For here’s the second thing with ideas. When you read a great book, a great story, you are not reading just an idea. You are reading countless hours of hard work, of thinking about how that small idea at the beginning of the process would turn into a novel, for example. And here’s the other thing I wanted to mention: an idea is a process. You develop the idea in the drafts that you write, in the constant thinking about how the idea plays out. The idea is never a finished entity ꟷnot until you publish, I think. And, by then, it’s quite likely that the idea bears but a tiny resemblance to the book that you have. When you look at a tree and you look at the seed that originated it, when you compare them, they seem to be completely different things. And yet, they are the same. It took, in the case of my novel, more than ten years for the seed to become a tree. A decade for the idea to become a book. I didn’t work constantly on the idea. I mean, I didn’t turn on the computer and work on it all the time. But my brain did. Both consciously and unconsciously. That’s why, suddenly, there were a couple of days in particular where I felt I had had a breakthrough, a gigantic couple of steps where I had gained understanding of what the idea was. A gigantic step to see this thing that Cortázar mentioned: that the story existed. It was like entering a big room that’s dark, and you don’t get to see very well. But you start finding ways to illuminate it. You turn on some lights. And so you know. You see windows, furniture, paintings hanging on the walls. I think Henry James said something similar about writing characters. So, in the end, our relationship with ideas continues to be a mystery. Are they our own creation? Are they something waiting for us, if we are persistent enough? Are they some kind of coworker, of partner that the writer has to function with? I don’t know. I know I am paying attention. All the time. And I know, also, that, no matter what, I will persist. And, if I’m lucky, I will also prevail. Federico Ivanier

By Nicola Garrard

•

September 7, 2023

In 2014, I read a news article about the suffering of separated child refugees in Calais whose numbers had risen to nearly a thousand. I found it shameful that just twenty-one miles from the coast of Britain there were children and teenagers living in tents and makeshift shelters in the degrading cold, filth and disease of a refugee camp called ‘The Jungle’ and along the Pas-de-Calais coast. I started to collect donations of food and essential clothing with the help of other parents at my children’s primary school, teachers and students at the secondary school where I taught – (many of whom were themselves refugees or the children of refugees), and an Ethiopian restaurateur from South London whose teenage daughter had campaigned for period products to be given to women and girls in the French camps. Then I filled my small camper van to the roof and took the Eurotunnel car-train to Calais on a number of occasions. In Calais, I volunteered with a grassroots French refugee charity, distributing meals and spending time talking to young refugees. Sometimes these were unexpected conversations, like a discussion with a young Iranian about French revolutionary history, and with a young Syrian about Shakespeare’s plays in the camp’s library, ‘Jungle Books’. There was always the obligatory question of which football team you support and kickabouts happening all over the camp, bringing smiles to otherwise down-hearted young people. I also met many local French people who had resisted the far-right’s propaganda of fear and opened their own flats and homes to refugees to take showers, charge their mobile phones and share family meals. On one occasion, I met a small thirteen-year-old Eritrean girl in Calais who begged me to take her to England where she had family. Fearing for her safety, I desperately wanted to help her find her family - perhaps smuggling her on the Eurotunnel in one of the many hiding places my children loved in our camper van. I didn’t agree to take her. People-smuggling is against the law; I might have lost my career, been fined and sent to prison. We swapped phone numbers and promised to keep in touch. In the end, that was the right decision. As I was a known volunteer in Calais, the border authorities strip-searched my camper van as I returned home. My next visit was the last as the French government made it clear that UK aid volunteers were not welcome and were often refused entry. I am sure that a younger, more impulsive version of myself would not have thought twice about trying to help the girl I met. I often think about her and hope she found her family and safety; not long after we swapped numbers, her phone line went dead. Years later, I was left with the ‘what if’ of her request and it became this story. Since 29 Locks was published, readers often ask me what happens next to Donny. He remained so alive for me that I had been asking myself the same question. I decided to connect these two stories of dislocation, injustice and separation, and see how Donny would respond to meeting the young refugees who had made such an impression on me. Would his bravery, openness and sense of justice make a difference? And what could we learn from teenagers who have travelled across the world to find safety and family? Nicola Garrard West Sussex, 2023

By Igiaba Scego

•

August 30, 2023

Salem, Massachusetts is the birthplace of illustrious figures, including writer Nathaniel Hawthorne. And for me the most important of these is Sarah Parker Remond, an obstetrician, human rights activist and feminist; a woman of great culture, a Black woman who sought freedom at a time when this was difficult for Black people (and for women), in the United States and elsewhere. Sarah was born in Salem and died in Rome on 13 December 1894, aged just 68, in a hospital that no longer exists, the Hospital of San Antonio. I heard Sarah’s story from a friend. I never imagined that such a talented and headstrong woman could have lived in and so loved the city of my birth. A Black, feminist woman. I remember looking closely at her photograph. There was Sarah - though I didn’t yet know her name - in a Victorian-style dress, plain and high-necked. I don’t know why, but I had the impression this was a woman who could assert herself when necessary. My friend gave me a quick rundown of what she knew of Sarah’s story. Her parents were activists, free Blacks from Salem and at the forefront against racism; educated people, well-read and committed. For days on end, I imagined this woman, who left the United States first for England and then Italy, roaming free and delighted in the streets of nineteenth-century Rome. I saw myself reflected in her as if in a mirror. And so, like a bloodhound, I began to follow her trail through the city. My friend Cristina had told me Sarah was buried in the Protestant cemetery, and I began to find myself there with increasing frequency, seemingly by chance. There’s nothing left of her now, except a plaque. But just knowing her name was there among all the others filled me with joy. It was at the cemetery that I first wondered whether Sarah Parker Remond knew Edmonia Lewis. She - Edmonia - was my other obsession. I’d read many books about her. Edmonia’s life was not a happy one… always short of money, growing tension with her patrons, the desire to take flight, Rome, financial hardship and, at last, success. Edmonia suffered greatly to make a name for herself, and she finally accomplished it. And when I saw the photo of Sarah, I asked myself whether these two free Black women had known each other in Rome, that brand new capital of the kingdom. And, in fact, their paths did cross. They met and they spoke together. When the well-known writer and activist Frederick Douglass visited Rome with his wife, they both met him. Edmonia was his official guide, and took the Douglass family walking through the streets of the city center. So even now the book’s finished, from time to time I dream of these three Black people - Edmonia, Sarah and Frederick - exploring Rome. Three Black Americans, three people whose determination changed the world, walking about the Eternal City. Happy and free. But for these two women - and this should be furiously emphasized - Rome also had extra significance. In the United States, both had been subjected to intense aggression. Edmonia had been beaten (and according to some biographies, raped too - but we know nothing for certain about this) outside the boarding school she attended, and Sarah was thrown down the stairs in a theatre during a play she was keen to watch. The theatre was packed, and Sarah was punished - like an ante litteram Rosa Parks - because she refused to give up her seat for a white person. She wanted to stay seated: it was her right to do so, she had paid just like everyone else. So she did not move from her place. When I found out that in the nineteenth century two women (Black women, what’s more) had chosen Italy as their place of freedom, I was so moved that my eyes literally filled with tears. Italy rhymed with welcome, dreams, opportunities, not hate. And these two women were travelers, Black women who journeyed across oceans (the same ocean that had seen so many Black people in shackles) and cities. Black women whose bodies had torched borders and prejudices. And it was inevitable that during the conception of the novel and its writing, I would think about what was happening in the present day in the Mediterranean, between Europe and Africa. People dying on boats or in Libyan detention camps, people denied visas, denied legal travel with a passport and a suitcase. The idea of a Rome that allowed women to be free is the image that helped me to write this book. All the women in the story, to a greater or lesser extent, are struggling against a patriarchal system that’s crushing them. Love is impossible without freedom, my protagonists believe. And they get by as best they can. Some fight to love men, others to love women; others embrace a solitude that’s chosen. Igiaba Scego Rome, 2023

By support

•

July 3, 2023

I’m so happy that my mother’s incisive, beautiful books are being rediscovered by a whole new generation. As well as being her daughter, I am her literary executor. And so it felt very timely to be discussing her writing at the Jaipur Literary Festival at the British Library last month as we approach the 100th anniversary of her birth next year. Internationally acclaimed, her work fell out of print towards the end of her life, and with the republication of Nectar in a Sieve by Small Axes, her astonishing first novel, her novels are now reaching the status of classics. Please do join us in celebrating the enduring appeal and legacy of Kamala Markandaya’s work. Nectar in a Sieve was the first novel written by my mother, the Indian novelist Kamala Markandaya. It was originally published in 1954 in London, the city my mother had moved to in 1948, and it received instant acclaim. It was swiftly bought by the American publisher, John Day, and was then selected by the Book-of-the-Month Club, a prestigious honour guaranteeing sales – and fame. Her book was translated into seventeen languages. It is still taught in schools and colleges in India and the USA – a remarkable achievement after seventy years. I’m delighted that HopeRoad are now republishing it in the UK. Reviews at the time of first publication were ecstatic. ‘A novel to retain in your heart’, sighed the Milwaukee Journal . The New York Times thought that ‘Nectar in a Sieve has a wonderful quiet authority’. To quote Penguin India’s Modern Classics edition: ‘Few novels ever published have celebrated the human spirit, its sheer resilience, with greater success.’ All true, I think. The central love story of the novel, the love of Rukmani and Nathan, which survives many tests and endures to the end of life, is deeply moving. Nectar in a Sieve was published seven years after India gained independence. India had been a British colony for three hundred years, ruled by a British administration with puppet maharajahs concerned with enriching themselves. The large rural population had few resources to tide them over difficult times; simply surviving occupied their time, while the wealth of their country drained away to Britain. Central to 20th-century history was Mahatma Gandhi who rose up against this oppression. He had the support of the people, and in 1947 the long British occupation came to an end. To my mother’s generation this struggle was at the centre of their lives. It was acknowledged among the leading writers of the time that what they should depict in their work was the lives of India’s poorest people. Markandaya tackled this head-on, basing her book on her close observations of rural life in the country where she had grown up. She gives a voice, not just to a peasant, but to a peasant woman – an unheard voice. She shows Rukmani happy in her own life, loving her husband and children and responsible towards them; sensitive to the rich natural environment around her as she tends her crops; literate, uniquely among her peers; spirited, and yet so vulnerable to the vicissitudes of life, because she is completely dependent on the forces of nature, and other human beings, perhaps hostile. If the harvest is bad, the family will go hungry, as they have little spare money and no help. If their land is repossessed, they will have nowhere to grow food and no source of income. Markandaya writes with a fluid, polished, gentle style that disguises her hard-punching message. In the background of the novel is the knowledge that India is about to change: a lifestyle of poverty and acceptance that has gone on for centuries is about to be invaded by the modern world bringing with it the onslaught of capitalism. And Rukmani’s children are angry… The novel is such a page-turner, you can’t stop reading it, for the bittersweet, tragic story, the beautiful descriptions of the Indian countryside, and the remarkable evocation of life in an Indian village seventy years ago. Kim Oliver June 2023

By support

•

June 1, 2023

In my early teens I became aware of a strange phenomenon in my neighbourhood. On the August bank holiday, groups of Caribbean women could be seen walking in the middle of the road to some unknown destination. Always colourfully dressed, they tended to be Dominican or St Lucian and chatted away in French patois, which was incomprehensible to me, a Jamaican, but recognisable because I lived next door to a Dominican family. These people were, I learned eventually, heading to Ladbroke Grove. Soon I too joined the annual pilgrimage to the Carnival in the Grove, now universally known as the Notting Hill Carnival. On the 75th Windrush anniversary, the extraordinary event that is the Notting Hill Carnival, will, I hope, be accorded the recognition it deserves as one of the greatest gifts to Britain by the Windrush generation. Like many early carnival goers, I probably found the event attractive because, as a member of a racial minority, it gave me an opportunity to be in the majority, if only for a day. But it was clearly a majority with some deep-rooted grievances, the spontaneous expression of which gave the event an unpromising future. I remember being trapped beside a sound system in the shadow of the Westway flyover watching dreadlocked black youths throwing bricks at a line of policemen while dub music, or Burning Spear bellowing in his hoarse voice ‘Do you remember the days of slavery?’ issued from a twelve-foot-high wall of huge speakers. Given that many British institutions have in recent years expressed recognition of, and regret for, their involvement in the transatlantic slave trade and slavery, the sound systems, Rastafarians and reggae musicians were clearly ahead of their time. Their 1970s message should be included on any list of Windrush legacies. Carnival continued to be unpredictable and combustible into the 1980s, but it also became more popular, drawing participants from far and wide. As its complexion changed, I came to appreciate its unique creativity, which can only grow bolder and more imaginative with greater sponsorship. The art of carnival, as the Brazil and Trinidad carnival have shown, is inexhaustibly rich. This year I will probably be even more appreciative of the Notting Hill Carnival as a celebration not of race but of a vibrant multicultural Britain, a nation of cultural diversity most visible in major cities, the effect of post-Second World War immigration. Britain has seen several spectacles in recent years: Queen Elizabeth’s jubilee and, most moving, funeral, and King Charles’s coronation. Staged in Britain’s inimitable grand style, these royal events, though far more inclusive than they have ever been, nevertheless reinforced an unchanging elitism, the inevitable result of any form of royalty. The Notting Hill Carnival offers a different kind of spectacle. It’s a collective celebration that brings millions of visitors to the streets over two days. At carnival all participants are equal and, in the spirit of playing mas, even the most ordinary men and women can be crowned kings or queens for the day. And that perhaps is the Windrush’s greatest legacy as expressed through carnival: the power of the human imagination to free ourselves from the rusty chains of tradition. Ferdinand Dennis London 2023