Welcome to the HopeRoad Blog

Bringing you regular blog posts penned by our authors and editors.

Enjoy!

By support

•

November 4, 2024

I wrote The Wild Ones with memories of my adolescence as part of a violent community in my hometown of Monterrey, and also with the memory of a very complicated area on the outskirts of my city that I got to know around that time. That place is called El Peñón, located at the foothills of Cerro de la Silla, an emblematic mountain of my city. The houses are clustered on the slopes, next to ravines, among the rocks. Poverty is severe there, and the needs are many. It's an ideal place for organized crime gangs involved in drug trafficking to recruit young people into their ranks. But at the same time, it’s a happy place; people live as they please, social relationships are as good and bad as anywhere else, and there are also boys and girls who, despite the poverty, choose to study and get ahead. The Wild Ones tells the story of a boy at a crossroads: his mother is unjustly imprisoned, and he must find a way to get her out—either through the regular judicial system, which offers nothing, or by joining forces with the drug trafficking gangs, who at least promise to protect his mother in prison. And it's also about the main character, Efraín, and the relationship with his siblings and the choices they make along the way. As this unfolds, the novel portrays the city, what it's like to live in that area, and the struggle to escape poverty—all seen from two perspectives: the raw, real view of the drug world among young people, and a festive, casual, joyful view that shows what it's like to live and push forward from that situation. The Wild Ones will take you through a world beyond the bleak context of Latin America's large metropolitan cities, leading you on a journey that is real, rough and sad, but also as joyful and hopeful as books can be. Also, I'm thrilled to be part of HopeRoad and to have the novel reach an English-speaking audience with the support of an English PEN Award! Thanks to my editor, Rosemarie, and my translator, Claire, for everything! Time to celebrate. By Antonio Ramos Revllias November 2024, Mexico The Wild Ones was published October 24th 2024 You can find your copy here .

By support

•

October 22, 2024

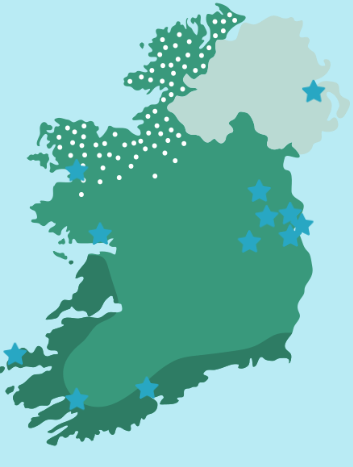

To celebrate the publication of Cauvery Madhavan's The Inheritance , author Cauvery Madhavan has chosen her favourite Irish bookshops to highlight for this year's Irish Book Week 2024. You can explore the map of these bookshops on our dedicated Google Maps , as well as the list below: Cauvery Madhavan's favourite bookshops No Alibis Bookstore ( @NOALIBISBOOKS ) Botanic Avenue, Belfast Antonia’s Bookstore ( @AntoniasBooks ) The Gate House, Navan Gate, Townparks North, Trim, Co. Meath Tertulia Bookshop ( @TertuliaBooks ) West Port, County Mayo Kenny’s Bookshop & Art Gallery ( @KennysBookshop ) Liosban Business Park, Tuam Rd, Galway City, Co. Galway Chapters Bookstore Dublin ( @chaptersbooks ) Parnell St, Dublin 1, Co. Dublin Gutter Bookshop - Dalkey ( @GutterDalkey ) The Gutter Bookshop, 20 Railway Road, Dalkey, Co. Dublin The Maynooth Bookshop ( @MaynoothBooks ) 68 Main St, Maynooth, Co. Kildare Ravens Books ( @ravenbooks ) 34 Main Street, Blackrock, Co. Dublin Woodbine Books ( @WoodbineBooks ) Lower Main Street, Kilcullen Hodges Figgis ( @Hodges_Figgis ) 56-58 Dawson St. Dublin 2, Co. Dublin Bantry Bookshop ( @BantryBookshop ) William St, Town Lots, Bantry, Co. Cork Vibes and Scribes ( @vibesandscribes ) 21 Lavitt's Quay, Centre, Co. Cork The Nenagh Bookshop ( @NenaghBookshop ) Nenagh North, Nenagh, Co. Tipperary Dingle Bookshop ( @DingleBookshop ) Green Street, Dingle, Co Kerry Explore Cauvery Madhavan's titles The Inheritance and The Tainted .

By support

•

September 18, 2024

In the summer of 1999, I drove over the Cousane Gap and, cresting the narrow mountain road, laid eyes on Beara for the first time - the glory of its mountains, valleys, forests and bays stretched all the way to the distant horizon. I was in West Cork to make a start on this thing called writing-a-book that I’d been stewing over for ten years or more. By the time I got to Eyeries at the tip of peninsula, I was head over heels in love. Huge banks of clouds roiled over the Atlantic before scudding across the shimmering expanse of Bantry Bay. In the embrace of the seascapes lay vistas that were in equal measure peaceful and inspiring as they were wild and distracting. It wasn’t long before I discovered that natural elements are the most temperamental of artists - their seasonal whims, their daily fancies, their hourly moods paint, sculpt and colour Beara with wonderful abandon. There is something about the untamed landscape, it’s geological formations and fantastical mountains extruded like slabs of untidy Viennetta, folded, scrunched, squeezed and hewn by volcanic and glacial activity millions of years ago, that energizes from within. The precious pockets of ancient Atlantic rainforest that dot the peninsula, pristine beaches and mystical standing stones come together to form a creative cocoon. Now, twenty five years later I know that my writer’s heart and soul has lived its best life in our small mountainside cottage on the Caha range. There is a peace and quiet that frees the mind though the views are actually very distracting and my writing is usually done facing a blank wall! Being a writer leaves you prone to periodic bouts of writer’s block. This is good because it allows you to be creative with the solutions. They don’t have to be sensible or logical, they just have to work. There is no point in telling a writer not to procrastinate - that’s like telling a monkey not to scratch. It doesn’t help to ask a writer to get a grip, we might let go of the only straw we are clutching at. After all, if you have writer’s block at least it affirms your belief that you are a writer. My solution is to immerse myself in the Beara landscape, to let its ancient magic work on my senses. The old sash windows may be single-glazed, with stiff catches and beads of condensation glinting in the early morning sun, but beyond it is the Ireland I love. Downhill from the house, the Glengarriff river rumbles over a huge rocks, moving swiftly past banks of sally willows in a headlong rush towards the harbour at Blue Pool, a few miles away. The green collage of hillside pastures often fades away behind a fine mist and bands of rain follow, driven in sideways sheets by a whippy wind. Yet a clearance from the West is inevitable, rainbows arch across the valley and the writing begins to flow once again. Coming from India and now having lived in Ireland for nearly four decades, a double dose of national hangups colour my writing. The country of my birth and the country I call home have a shared obsession with family, religion, politics and not making a show of yourself. Stories thrive in this heady mix of plot possibilities and for the last twenty years while I wrote and published three other books, I constantly mulled over the characters in my new novel The Inheritance. Fascinated by the tragic history of O’Sullivan Beare and his people, I was determined to work that story into a thread that ran through the book. I finally began writing it during the first few weeks of the Covid pandemic, using our own cottage as the setting. Then, in the break between lockdowns, having decamped from Kildare to Glengarriff, I stumbled across the most incredible piece of information that literally made my hair stand on end. The narrow and remote mountain ridge on which our cottage is situated actually straddled the ancient battlegrounds of the very siege that I was trying to weave into my story! This discovery, that in the winter of 1602, the English army had camped in the swampy forests in the valley the left of our cottage, while in the valley to the right, O’Sullivan Beare and his followers had remained hidden for six months, was exactly the sort of impetus I needed to spur my writing on. From thereon, I felt that I had to and was meant to write this book, to honor the memory of those many hundreds who perished in what is now the Glengarriff National Forest. Writing might be a solitary pursuit but I believe not much is achieved in isolation. In Beara, I’m lucky to be surrounded by friends who are very protective of my writerly ambitions. This really matters because most writers, some time or the other, are just a sentence away from throwing in the towel. My immediate neighbours have been incredibly supportive and if I headed into Caseys in Glengarriff, Donal Deasey the landlord would inevitably give me bits of information, both historical and contemporary, that added to the scaffolding of my novel as it progressed. It doesn’t surprise me one bit that a thread of magical realism runs though The Inheritance - conceived in Beara it could be nothing else! by Cauvery Madhavan The Inheritance publishes September 19th

By support

•

July 15, 2024

Are we who we are because of the country we were born in, the parents we were born to, the social class we belong to? Or is it because of our lived experiences, our childhood, the things that happen to us and shape our lives? Or is there something else beneath it all, something deep down, a distinctiveness that defines us and makes us unique? These are the questions that led me to create The Darkness of Colours . I have always questioned the decisions I take, wondering whether I am making choices based on my own authentic will or whether I am influenced by factors I have not chosen. Sometimes it is hard to tell these things apart. For example, I love mate (pronounced, mah-tay). Mate is a herbal infusion, drunk from a round bombilla using a metal straw, and it is a very popular drink here in my country, Argentina. In fact, as I write these words, I have a mate on the table next to me. Given this is a local custom, little known beyond Argentina and Uruguay, if I had been born elsewhere, I might not even know it exists. I wonder then, do I like mate because I truly like mate , or do I like mate because we Argentinians drink it from the moment we get out of bed? I believe in the power of fiction and the power of questions, and I like to combine them. It’s 1885 in Buenos Aires. A man kidnaps five babies and embarks on an experiment: to raise each child in a different way and observe the results. In order to avoid any sentimentality, rather than a name, he gives each child a colour: Green, Blue, Black, Brown and White. They are cruel experiments. One of the children is brought up to believe he is a dog. Another is deprived of daylight and forced to fight against wild animals. Twenty-five years later, the kidnapped children return, but they have no memory of where they have been. A journalist is brought in to investigate and as he starts to delve into the case, the perpetrators of the experiment begin to turn up dead. This is a brief summary of the plot of The Darkness of Colours and, as I previously mentioned, my desire was to write about this elusive topic called identity. My initial plan was to write a short story, but I soon realised I had enough ideas to make it a full novel. I thought it would be interesting to situate the events in the past, specifically at the turn of the twentieth century, in part because carrying out the same experiment today would involve topics such as genetics and other technological issues which I was not so interested in discussing. For me, these years – 1885-1910 – are also among some of the most interesting in human history. It is a moment of great scientific advancement, during which a large part of the modern world as we know it today was configured. It is the period when the avant-garde emerged, when artists decided a picture can show more than what we see with our eyes alone, when musicians began to abandon traditional harmonies and writers realised that a novel or a tale can do more than simply tell a story. And to that we add the arrival of cinema, psychoanalysis, Marxism, ultimately new ways of viewing the world that still influence us today. They were years when the word “progress” was used for everything, where humanity placed all of its hopes in a future which, just a few short years later, would be shown to be not quite so brilliant. This was therefore the perfect moment for a man like Andrew to embark on his experiment in search of discovering the true capacity of human beings. I decided the novel would open and close around the festivities celebrating the first centenary of Argentina as a nation in 1910. Are countries themselves not great experiments? At times, that’s how it feels here in my country, at least. Argentina is a country where immigration plays a fundamental role. Around the turn of the twentieth century when the book is set, thousands of people from across the globe – most of them poor – arrived in Argentina with nothing but the hope of making themselves a future in the “New World”. That’s how it was for my family. My grandparents and great-grandparents belong to that world of immigrants I describe in the novel. My paternal grandfather came from Spain with absolutely nothing at the age of just 14. In the same way, my maternal great-grandfather arrived from Italy. I am a product of this immigration. I have included many details about the difference spaces in my city, about the architecture. I decided to use the same streets where I live, the old part of Buenos Aires, and I had to spend a lot of time investigating how my city was back then. It was great to walk the streets I have walked along my whole life, dreaming about how they might have been more than a century earlier. If I am honest, I never thought that this book would reach so many readers so far away. To my surprise, it is now being read in many countries with identities and customs that are completely different to my own (countries for example, where they don’t drink mate ). For me, it is a story so deeply tied to my city that I struggled to believe that anyone outside it would be interested in reading it. Perhaps we are not so different. Perhaps the important questions are the same. I am immensely grateful to anyone who decides to read this book and I hope you enjoy the story. While it is completely fictitious, at the same time it is a postcard from my country, my city and our history. In all its colours. And all its darkness. By Martín Blasco Argentina, 2024 Translated by Claire Storey The Darkness of Colours - July 18th

By Federico Ivanier

•

October 11, 2023

Sometimes people want to know where writers get ideas from. That question always gets me thinking. Where do I really get ideas from? I also ask writer friends the same. I get the impression, every time, that we don’t really know. It’s part of the mystery of writing. And it’s great that it is so. I don’t believe there’s a mechanism to get ideas. Or some kind of imaginary pond, where we can fish a silvery, slippery fish-idea. That would be great, since I would know, as a writer, that I definitely will get new ideas. Because, the truth is that, after I finish one book, I never know if I will write another one, if another idea will be good enough. There’s this unpredictability that writers have to deal with. Once you know, say, how to drive a car, you can drive any number of cars. Once you write a novel, it’s safe to say that it’s unclear whether or not you will be able to write another one. Or, at least, one that you (and publishers) think it’s worth publishing. I have come to think that somehow - maybe - the process is reverse. It’s not you getting ideas, but ideas getting to you. Argentinian writer/legend Julio Cortázar said that the stories that he wrote already existed and that his job as a writer was to turn them into language. So, it’s ideas that get you, not the other way around. That’s a funny way to think about it. It gives the impression that ideas are creatures that haunt or possess writers. At their own will, I might add. Which, of course, is the bothersome side of the deal. As for me, I find the idea both true and impossible at the same time. I am willing to accept that, within all that inexplicability of the appearance of the idea, there’s a part that is not up to the writer. That much I will admit. It doesn’t depend on how much you try to have an idea. It will come. Or it won’t. I would say ideas are, at least in my experience, a mixture of things. On the one hand, they are a state of mind. Let me explain. The very fact that you are in the world as a writer, that you never stop really working as one, or thinking as one, will arrange your mind in a certain way. You will perceive life not just of a set of experiences, but as a set of writing opportunities. For example: my girlfriend left me. I am devastated. It’s terrible. But wait a minute, surely I will be able to write about this at a certain point. That’s the great part of being a writer. You can use experiences to your advantage. If your mind is ready to think about the world in terms of story, you are ready to find it. That is, if your mind is searching (normally unconsciously), it’s bound to find something. That is very much the case with my novel Never Tell Anyone Your Name , beautifully translated by Claire Storey. The story came in a completely unpredicted manner. I was travelling with my then-girlfriend from Bordeaux to Madrid by train. In one point, we had to change from the French train to the Spanish train right on the border. When we were ready to get on our Spanish train, we discovered that the dates of our tickets were wrong: they were for the following day. Changing them for the train due to depart at four in the afternoon (the one we had plans to take) was impossible. It was the end of the holidays and the train was full. The best we could do was get a couple of tickets for the midnight service. So we were left with eight hours of nothing ahead of us. We were in a small town called Irún, which we had never intended to visit and my girlfriend certainly wasn’t interested in visiting. As for me, I was delighted. It was an unplanned event. It was a small event, all right, but unplanned. I decided to visit this place which was not precisely touristic. As I said before, my girlfriend was not really in, but it was worse to remain in the station, so we went. I knew, as soon as I was out, walking (it was a really cold day), that I was going to write about that. I didn’t know exactly what I was going to write, but I knew I would. That very moment was one that I was going to turn into some kind of story. I even took pictures, as we walked, to be able to remember the places we saw, the path we took. I was, already, in a way, taking notes. Of course, it was not that I had the idea ready just then. For here’s the second thing with ideas. When you read a great book, a great story, you are not reading just an idea. You are reading countless hours of hard work, of thinking about how that small idea at the beginning of the process would turn into a novel, for example. And here’s the other thing I wanted to mention: an idea is a process. You develop the idea in the drafts that you write, in the constant thinking about how the idea plays out. The idea is never a finished entity ꟷnot until you publish, I think. And, by then, it’s quite likely that the idea bears but a tiny resemblance to the book that you have. When you look at a tree and you look at the seed that originated it, when you compare them, they seem to be completely different things. And yet, they are the same. It took, in the case of my novel, more than ten years for the seed to become a tree. A decade for the idea to become a book. I didn’t work constantly on the idea. I mean, I didn’t turn on the computer and work on it all the time. But my brain did. Both consciously and unconsciously. That’s why, suddenly, there were a couple of days in particular where I felt I had had a breakthrough, a gigantic couple of steps where I had gained understanding of what the idea was. A gigantic step to see this thing that Cortázar mentioned: that the story existed. It was like entering a big room that’s dark, and you don’t get to see very well. But you start finding ways to illuminate it. You turn on some lights. And so you know. You see windows, furniture, paintings hanging on the walls. I think Henry James said something similar about writing characters. So, in the end, our relationship with ideas continues to be a mystery. Are they our own creation? Are they something waiting for us, if we are persistent enough? Are they some kind of coworker, of partner that the writer has to function with? I don’t know. I know I am paying attention. All the time. And I know, also, that, no matter what, I will persist. And, if I’m lucky, I will also prevail. Federico Ivanier